Jerzy Kulczycki was born in Lwów on the 12th of October 1931. His father Zdzisław, a judge, was arrested by the NKVD in March 1940 and was shot in Ukraine in still-unexplained circumstances and at an undisclosed location. Together with his mother Maria née Baternay, Kulczycki was deported on the 13th of April 1940 to Kazakhstan. In August 1942, along with General Anders’s army, he left for Persia where he went to school. On the 1st of January 1944, he was accepted into the Young Leaders’ School and a month later he was transferred to the Cadet School in Barbara Palestine, where he received military training. In August 1947, together with the whole school, he arrived in Great Britain.

He finished his secondary schooling at the Young Leaders’ Cadet School in Bodney, and was accepted into the English-language Joseph Conrad School at Haydon Park, which had been set up specifically for Polish soldiers. He took his school-leaving certificate there, and was accepted into the University of London to read engineering. He graduated in 1954, and in 1958 he qualified as a civil engineer. While a student, he had played an active part in the Union of Polish Students Abroad, holding a number of positions on the world-wide board, and serving two terms as president. He earned a master’s in civil engineering. He joined the Polish Labour Party and remained a member of its top leadership until the founding of the Third Polish Republic.

In August 1958, in Nottingham Cathedral he married Aleksandra Lichtarowicz, who henceforth would be a faithful helpmate in his professional and community activities.

In 1964, he founded the Odnowa publishing house on behalf of the Labour Party, running it until its closure in 1990. Odnowa produced around 100 books, including works by Jan Nowak-Jeziorański, Józef Garliński, Zbigniew Siemaszko, and one of the most famous émigré books published – Jan Ciechanowki’s The Warsaw Uprising.

In 1972, he and his wife bought the oldest Polish bookseller in England, Orbis, which they ran under the new name of Orbis Books until 2008. In the mid-eighties, Orbis’s turnover was fifteen times greater than it had been before, and the bookshop employed ten people. The bookshop ran stalls in the Polish Hearth and in St. Andrew Bobola Church. During the time of the Communist People’s Republic in Poland, Kulczycki attached the greatest importance to the legal and illegal shipment of émigré and Western publications to libraries and to private individuals in Poland and throughout the Soviet bloc.

In the seventies and eighties, he devoted a great deal of time to reviving the activities of the Association of Friends of the Catholic University of Lublin and to helping the University. He played an active part in the founding of the Institute of Polish-Jewish Studies, in the activities of the Polish Hearth and in raising bursaries for Polish refugees.

He was decorated with the Knight’s Cross, the Officer’s Cross and the Commander’s Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta.

In Memoriam by Jarek Garliński

"I’m not too old to have silly ideas.

"I’m not too old to have silly ideas.

A few Christmases ago I was doing some research at the National Archives at Kew and the Kulczyckis, who live about three miles away, offered me a room for a fortnight. I then thought that it would be a really neat idea to go to the Archives by bicycle. In winter, mind you, along Chiswick High Road. Those of you who know the area are already looking at me as if I must be some kind of lunatic.

In any event a dear friend of mine duly procured a bicycle, security chain, clips, bone dome and all the impedimenta of the modern urban two-wheeled warrior. I had earlier e-mailed Jerzy Kulczycki to ask if it would be alright to keep the bike at their house. “Of course,” he replied. I inquired no further; I assumed that it would simply go in the shed in the back garden.

Well it didn’t. In fact the Kulczyckis told me to leave it in the hall. In the hall? Those of you who know the Kulczyckis’ hall are aware that it is a typical narrow hall for a London house of that period. For two whole weeks my hosts uncomplainingly squeezed past my bike carrying their shopping and going about their daily business. Not a word of complaint; not a reproach. Just a smile and an assurance that this muddy monster standing there like a bad piece of modern art was perfectly welcome in their home.

Now, in the big scheme of things this is hardly an issue of major importance and yet it so wonderfully illustrates the Kulczyckis: kind, thoughtful and always putting the interests of others before their own.

There are those who are more qualified than I am to speak of Jerzy Kulczycki’s work as a publisher and a bookseller, his day-time job as a civil engineer, his involvement in Polish community affairs and his work for the Catholic Church. Indeed, a simple enumeration of these various facets of his life shows just how versatile a man he was. He once confided to me that he would have been unable to do all of these things, had he needed more than the four hours of sleep a night that he could squeeze in.

But, my friends, I want to focus today on Jerzy Kulczycki the man.

I only came to know Jerzy Kulczycki over the last 10 years or so. Our paths had not crossed much before, but in the last two years of my late father’s life Jerzy Kulczycki and his dear wife became absolutely indispensable friends of my family and a wonderful support to my father in his declining years.

Casa Kulczycki is about ¾ of a mile from where my parents’ home used to be, whereas I live most of the year in the United States. With the best will in the world I could not be in England all the time. Yet, in those final years of my father’s life (my mother having died some years earlier) nothing was ever too much trouble for Jerzy and Alexandra. This involved dealing with doctors and the NHS, it meant helping with many of those logistical and bureaucratic matters with which my father’s housekeeper, who spoke no English and did not drive, needed assistance. It involved responding to calls from my father, including one (a false alarm as it happened) in the wee hours of the morning.

It was then that I came to appreciate Jerzy Kulczycki’s indefatigable goodness and generosity. I came to appreciate his kindness, his thoughtfulness and his immense fund of practical, good old-fashioned common sense. I saw him deal with difficult people with a deft touch. There was strength and determination behind those twinkling eyes.

In those years, when I came over from the States I would usually stay at the Kulczyckis’ and entering their house I felt that I was coming home, even though I was not a member of the family. I was immediately made to feel welcome, cups of tea, and at times something stronger, were immediately placed before me. Indeed the cups of tea kept coming and coming. No complaints from me there!

Yet my father and I were not alone in benefitting from the Kulczyckis’ hospitality and generosity. Many times during the evening the phone would ring at Casa Kulczycki and it would invariably be ‘sprawy społeczne’, community issues, with which both the Kulczyckis were deeply involved. There would as often as not be at least one other person staying in the house, sometimes more than one. We all shared the same bathroom, which the Kulczyckis were again only too willing to relinquish.

Only a few months ago when I went over to see them, Jerzy apologized for no longer being able to offer me accommodation for the simple reason that a team of carers had moved into the house. His first reaction was still to think of others.

I recall too his enormous bravery during his final illness. After I had been round to their house one afternoon about a year or so ago, Jerzy’s son Andrzej, who lives in the States, e-mailed to ask whether his father had mentioned his teeth. I replied that he had not. It transpired that the previous day the hospital had had to extract six or seven teeth, I believe it was, for medical reasons which I don’t really understand. Yet Jerzy had uttered not a word of complaint, even though he must have been in considerable pain. There was not an ounce of self pity in the man.

He also had something which is perhaps rarer among Poles of his generation, who saw too much of life’s harsher side far too young: a puckish sense of humour. I will always remember that little grin of his and that smile…that smile.

That impish sense of humour even extended to those harrowing times when he and his family were deported by the Soviets in 1940. Jan Gross in his book on the 1939 Soviet invasion of Poland Revolution from Abroad, quotes Jerzy as saying that, as a small boy of nine, he had actually found the whole experience rather exciting. When I asked him about this a few years back he concurred with his original view saying that it had indeed been exciting initially and that the children had had all sorts of freedom. After all, how many nine-year-olds dream of not having to go to school, and for months on end as well?

Jerzy had a way too with words. Some years ago we were having dinner in Warsaw and the conversation turned to my late father whose final publisher Jerzy had been. I remarked that my father always quarrelled with all his publishers, but that, from what I could tell, he and Jerzy had never quarrelled. Jerzy turned to me and grinned: “Of course we quarrelled,” he chuckled, “but your late father was a marvellous man to quarrel with.”

Jerzy was a man of many parts. Living in the US I have been able to witness a side of him of which perhaps people here in the UK know less. For upwards of thirty years or so he and Alexandra would travel each year to the States to attend the annual conference of what has now become ASEEES: an unwieldy acronymic mouthful concealing the umbrella organization in the United States for all things Slavonic or, as Americans would have it, Slavic.

Two years ago the two of them travelled for the last time to such a conference in Washington DC; she with one artificial knee and the other one giving out; he after by-pass surgery and already in the first stages of his final bout with cancer. They had been going each year to sell books, but also now to witness the awarding of the prize which they had funded. Its full name is the ASEEES Kulczycki Book Prize in Polish Studies (formerly the Orbis Prize) and it has been awarded annually since 1996 for the best book in any discipline, on any aspect of Polish affairs. The recipient of the prize that night in DC, Professor Antony Polonsky of Brandeis University in Boston, is here this morning in the church, having come up from Tuscany to be with us.

It was then that I saw firsthand the respect with which Jerzy Kulczycki is held in the Polish academic community in the United States. Since the news of his death was announced, a number of members of this community have been in touch expressing their sadness at being unable to attend today.

In his quiet, unassuming way Jerzy Kulczycki, with Alexandra by his side, has done the Polish cause an immense amount of good. Misinformation and bigotry are, in times of peace, combatted not with shouting and grand gestures, but by determined educational efforts and quiet persuasion. Thus I stand in total awe of someone who could publish upwards of 90 books in what, in essence, was his spare time.

On this day, then, my deepest condolences go out to Alexandra, Pani Ola, who has been a splendid partner (and I mean that in the very fullest sense of the word) to Jerzy for all these many years. My condolences to his children, Andrzej, Martha and Ryszard, who are all here, two of them having travelled from other continents, and to his grandchildren, who have understandably been unable to make the long trip from Australia and the USA.

I should like too to thank all those good people, most of whom are here today, who helped and looked after Jerzy Kulczycki these past few years: his indefatigable carers. Thank you. Dziękuję Wam bardzo.

My friends, we have lost a very, very decent man, ‘rzeczywiście porządny człowiek’, as we would say in Polish. All of us here today will of course remember him in our own way. Yet I for one will miss his warmth and his excellent judgement, both on matters Polish, and on people in general.

Jerzy Kulczycki’s contribution has been immense and his loss will be keenly felt by many. He has touched many lives and has enriched all of us by his kind and modest demeanour. He was, in every sense of the word, a real gentleman."

30 July 2013

© Jarek Garliński

"I’m not too old to have silly ideas.

"I’m not too old to have silly ideas.

Stefan Andersz joined the Polish Army Cadet Corps in 1932 and in 1938 moved to Warsaw to become a student at the Aviation Cadet School. He joined the Polish Air Force and came to England in June 1940. In December 1942 he was assigned to 302 ‘Poznan’ Fighter Squadron based at RAF Northholt.

Stefan Andersz joined the Polish Army Cadet Corps in 1932 and in 1938 moved to Warsaw to become a student at the Aviation Cadet School. He joined the Polish Air Force and came to England in June 1940. In December 1942 he was assigned to 302 ‘Poznan’ Fighter Squadron based at RAF Northholt. Pioneer in the outdoor clothing business whose Henri-Lloyd label developed the first truly waterproof and durable apparel for sailors

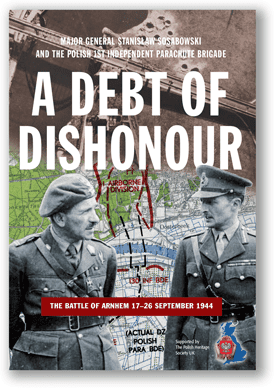

Pioneer in the outdoor clothing business whose Henri-Lloyd label developed the first truly waterproof and durable apparel for sailors Polish paratrooper who was decorated for his initiative during the disastrous Allied attack on the Dutch towns of Arnhem, Oosterbeek, Wolfheze, Driel and the surrounding countryside from 17–26 September 1944.

Polish paratrooper who was decorated for his initiative during the disastrous Allied attack on the Dutch towns of Arnhem, Oosterbeek, Wolfheze, Driel and the surrounding countryside from 17–26 September 1944. Dr Andrew Meeson Kielanowski MA, MB, BCh, BAO, KM, co-founder and Vice Chairman of the Polish Heritage Society (UK). A much-loved and widely-respected doctor in Hampstead, he was also a great philanthropist active in numerous charities. As Chairman of the Polish Knights of Malta (UK), he was a tireless fund-raiser for oncology clinics in Poland. He also played a leading role in the successful campaign for a Polish Armed Forces memorial to be erected at the National Arboretum.

Dr Andrew Meeson Kielanowski MA, MB, BCh, BAO, KM, co-founder and Vice Chairman of the Polish Heritage Society (UK). A much-loved and widely-respected doctor in Hampstead, he was also a great philanthropist active in numerous charities. As Chairman of the Polish Knights of Malta (UK), he was a tireless fund-raiser for oncology clinics in Poland. He also played a leading role in the successful campaign for a Polish Armed Forces memorial to be erected at the National Arboretum. Jan Walentowicz, who has died aged 90, flew Wellington bombers during the second world war and later became an RAF helicopter pilot. Born in Lida, then part of Poland (and now in Belarus), he was educated there and in Białystok. He joined the Polish air force for his national service. In September 1939 Germany invaded Poland.

Jan Walentowicz, who has died aged 90, flew Wellington bombers during the second world war and later became an RAF helicopter pilot. Born in Lida, then part of Poland (and now in Belarus), he was educated there and in Białystok. He joined the Polish air force for his national service. In September 1939 Germany invaded Poland. TADEUSZ W. SAWICZ Gen. Brg. Pilot Passed away on Wednesday, October 19, 2011 in Toronto at the age of 97.

TADEUSZ W. SAWICZ Gen. Brg. Pilot Passed away on Wednesday, October 19, 2011 in Toronto at the age of 97.